We come to Theodore Roosevelt National Park primarily for our up-close interactions with the bison, numbering upward of 600. Compared to Yellowstone, TRNP is tiny and quiet; there is an intimacy to it, especially this time of year. This allows the three of us to be closer to the Wilds, more so than any other place we’ve visited.

However, there are other reasons we love this park, which, in the summer, is the loveliest we’ve visited. It’s a fertile Great Plains scene nourished by the bisecting Little Missouri River.

I knew very little about Theodore Roosevelt until we started visiting the park named after him. But now, he also draws us into the loneliness of sparse North Dakota. Roosevelt lived, hunted, and healed himself on this land when he was young.

“And he gave them the ability to talk. We still believe they have spirits.

The animals can still talk to us through prayer. And through vision. And through prayer.”

The future president retreated from New York City after the shocking deaths of his first wife during childbirth and his mother, with whom he was extremely close, on February 14. Not only did these two women, whom he loved dearly, die on the same day, but they were also in the same house.

It’s impossible not to imagine the heartrending anguish young Roosevelt felt as he came to North Dakota to reclaim himself. The cabin he lived in was preserved and moved a few miles north into the confines of the national park.

Bison, once within a breath of extinction, were saved, in part, by Roosevelt, in conjunction with a handful of others. They are now ubiquitous in the park. Pronghorn, big horn sheep, prairie dogs, and wild mustangs are all easily seen.

This year, our interactions mainly were with two of the many bands of horses that roam within the park’s boundaries.

There are as many as 250 wild horses. They are less relaxed than the bison and can be skittish. In our seven years of visiting, it’s difficult to spend much time with the horses because they’d rather not be where humans are.

Luckily, we know of a couple of their hiding spots. And yet, even then, when we arrive, they disappear quickly.

I considered us blessed to spend thirty minutes with one of the bands. And how fortunate I am that Samwise and Emily are calm and quiet witnesses of all our wild brethren. Their gentleness and respect make it possible.

In all our visits, the late-morning half hour was the most time we’d ever spent with the mustangs. I cannot understand why they finally allowed it, but I felt such reverence for their company.

We spent our second night in the area in Dickinson, a 35-minute drive from the park. To reach the mustang bands, there is also a 48-mile in-and-out driving route. After our time with the wild horses, we returned to our hotel.

We were all tired. The trip has finally caught up with us, and we look forward to being at home in New Hampshire. I feel my body breaking down, and late-day chills are not uncommon.

It would have been easy to stay in our comfortable hotel room, but I forced myself to leave at 5:00 p.m. to spend two hours in Theodore Roosevelt National Park to enjoy the sunset. This also meant we’d have to push through the dark and get to bed later than I’d like.

It turned out to be one of the most fateful decisions of our five months away from Jackson.

We drove to the deepest part of the park and saw a few bison, a handful of mule deer, and a lone pronghorn. A shy band of horses trotted off when we pulled over to watch them.

We drove to Buck Hill and climbed to the top, where the sunset was fighting through the clouds.

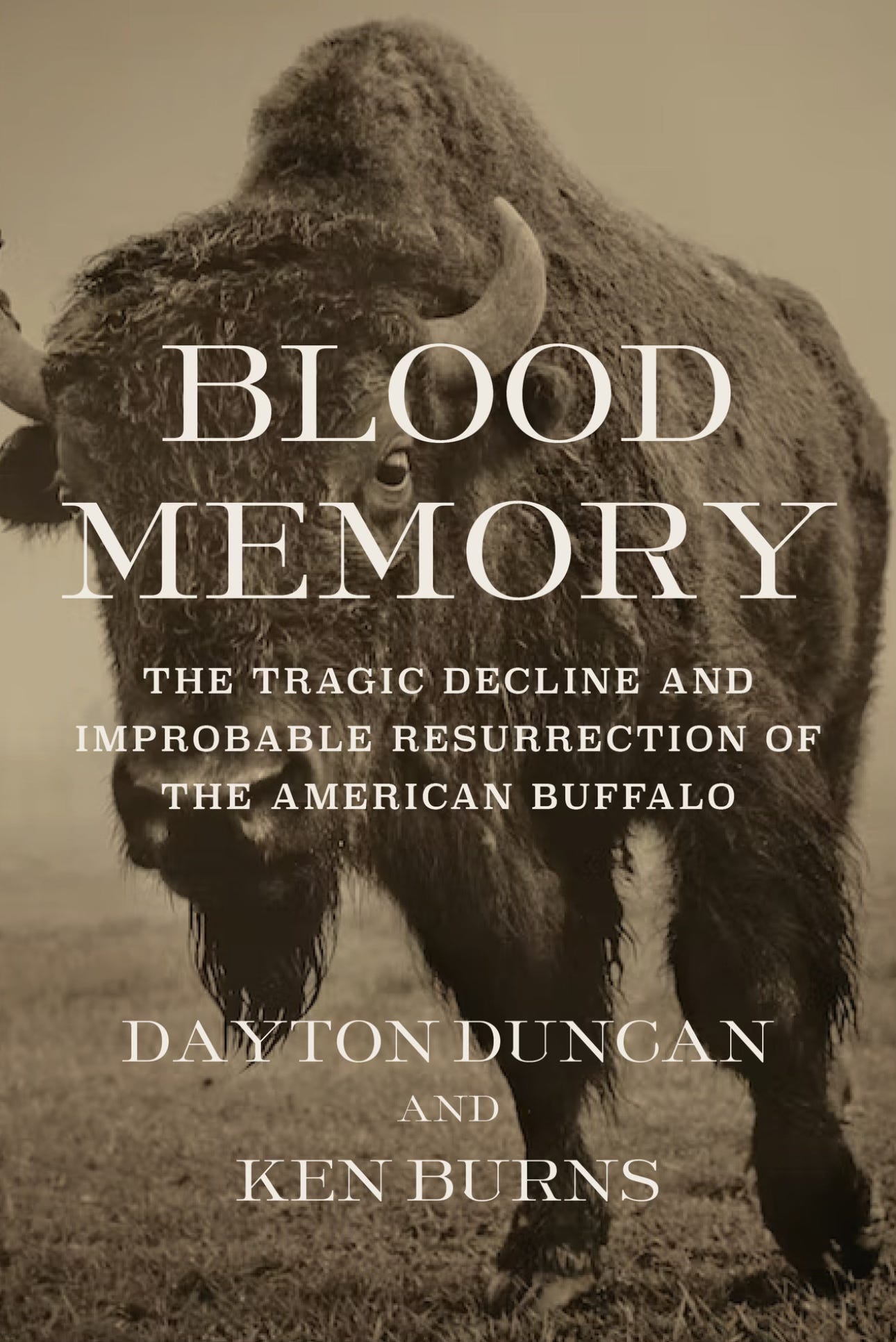

On our way from Yellowstone to Theodore Roosevelt, I had been listening to the audiobook companion of the recent Ken Burns PBS special about bison. It’s titled Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo. It’s authored by long-time Burns production partner Dayton Duncan.

Whenever I spend time at Theodore Roosevelt, it is an emotional experience. I’m bonded to this place in ways I cannot describe. But primarily because we can get so close to the bison. We spend hours with them, sitting silently, watching these 2000-pound bulls move as gently and powerfully as leaves on a stream. How can beasts so enormous move with a fluid grace? It defies logic.

We sat atop Buck Hill for a good while, partly because I wondered if we’ll ever return. Samwise is older now, and nothing is guaranteed. I felt sentimental and sad as I recounted all our visits. What hiking the White Mountains was to Atticus and me, these travels are to Samwise, Emily, and me.

Back in the HMS Beagle, I turned on the final chapter of Blood Memory, which was also emotional to listen to.

You could say I was in a trance as we drove slowly. The windows and sunroof were open, even in the chill air. Foreboding clouds parted, and sun and shadow splashed all around us.

There is a passage in the book that so moved me that I listened to it three times. It was a quote by now-retired National Park Service ranger Gerard Baker. Baker is a registered member of the Three Affiliated Tribes and the highest-ranking Native American in the National Park Service’s history.

“We believe that, when the Creator made everything, he put a spirit into everything, made them alive,” he told me. “Even the trees and the grass and the rocks and the rivers—everything, including the animals. And he gave them the ability to talk. We still believe they have spirits. The animals can still talk to us through prayer. And through vision. And through sacrifice.”

As we meandered along the snaking, narrow road, I listened to the passage again and again. And on the final listening, we rounded a giant butte and came upon a band of horses. Nine of them were dispersed on the right side of the road, from down low and spreading upward onto a hillside. They were grazing peacefully.

But what caught my eye was the lone white-speckled horse on the left side of the road. Her coat caught the late golden rays of the lowering sunlight, and she appeared to glow.

We stopped to watch her from a distance. She lifted her head, took note of us, and began to move through the scrub to get back with her companions.

When she reached the road, she trotted. But then, in a shocking move, she simply stopped in the road ahead of us and slowly turned to face us.

Face us?

The timing of Gerard Baker’s quote made me feel drunk.

Even the next day, when talking to a park ranger, she felt what followed to be unlike anything she’d seen in the park.

The horse watched us in stillness. Samwise and Emily crowded into the front passenger seat together in rapt attention.

The horse took a slow step toward us, then another, and another. I began videoing her approach through the sunroof, but also longed to take photos of her. Eventually, I put my phone down simply out of respect, to just be with her.

She was now so close that her front legs were against the Beagle’s bumper. And she stayed there, looking deeply into our eyes, one at a time. It was intense and peaceful, religious and beyond words.

How could it not be?

Richard Rohr wrote a fitting passage to our transcendent and mysterious moment.

“People who’ve had any genuine spiritual experience always know that they don’t know. They are utterly humbled before mystery. They are in awe before the abyss of it all, in wonder at eternity and depth, and a Love, which is incomprehensible to the mind.”

Yes, it was as close as possible to all of that. I was torn open; my heart lay bare before this incredible being. We looked into each other for twenty minutes, and as Gerard Baker said, we spoke through shared prayer.

Finally, she stepped back, gave us one last long look, and turned away and into the scrub to join the rest of her waiting band. I hadn’t been watching them. How could I take my eyes off of her? But now I could see that they had all gathered near and were watching the interaction in a tight pack.

This spiritual communion lasted for a stunning twenty minutes. It was only after we parted company with her that a handful of other cars passed us coming from the opposite direction. We’d been alone for the entire time.

This is why we travel alone, and at dawn and sunset, when the Wilds are out and most active. I long for these interactions—these undeniably impossible-to-comprehend moments. They rarely occur, and that’s what makes them even more potent.

Driving through the sudden darkness on the lonely highway, I was trembling and without words. I thought of calling a friend, but I knew I could ’t properly paint the scene or convey the moment’s weight and depth. So I stayed quiet and reflected. I did not sleep more than an hour that night. Instead, I lay in bed and thought of her eyes.

It was one of the signature moments of this coddiwomple and will never be forgotten. I will always remember this miracle in time when the most unlikely meeting between a wild mustang, two calm and accepting dogs, and one human.

Post Script

The horse is wearing a GPS collar, one of fifteen wild horses in Theodore Roosevelt National Park to have one. The collars are used to track movement and usage in the park.

This is the final unlocked letter of the trip. Feel free to share it—you know you want to. For paying subscribers, there will be at least six months of stories from this trip.